Claim Adjustment Form (Claim Increase)

Notice

This claim form and all claim amounts contained herein were prepared by my lawyer in accordance with the official Japanese legal guidelines, which unlike in the US, are strictly governed and limited to actual losses with minimal amounts allocated for suffering.

Heisei 19 (2007) (Wa) No.14582

Plaintiff: Wayne Michael Douglas

Defendants: X Clinic Representative YI, XX

Claim Adjustment Form (Claim Increase)

Tokyo District Court Civil 34, Koh-A Counsel Clerk’s Office

Sep 25, 2008

Plaintiff’s Legal Representatives: A

Associate: H

The Plaintiff hereby makes a claim increase in the said case as follows.

Top of Page

Clause 1: Post Demand Claim Increase

(1)

The defendants are to pay the plaintiff the sum of 30,928,848 yen, out of which, a penalty rate of 5% is to be charged against the sum of 25,350,650 yen for the period March 25th, 2006 to September 25th, 2008 (TN: 2½ years) and against the sum of 30,928,848 yen for the period starting September 26th, 2008 respectively until such time that final payment is made (TN: 3 years at court conclusion).

(2)

Legal expenses are to be borne by the defendants. Additional request for declaration of provisional judiciary and execution.

Top of Page

Clause 2. Cause for Claim Increase

2.1 Cause for Claim Increase (Prolusion)

The reasons for requesting a claim increase in this instance are because of an increase in losses / damages and a review of interpretations.

First, with regards to tangible loses (refer Complaint Form Clause 2, 1 (3) A [Pg 29] below), there are additions based on the discovery of supporting materials and increases in losses / damages through the progression of litigation.

Next, with regards to intangible loses (refer Complaint Form No 2, 1 (3) B [Pg 31] below), this was derived from a review of the base income after the stabilization of symptoms. (NB: Amendments are signified by the underlining of the changed amounts.)

Top of Page

2.2 Tangible Losses

Tangible Loses [¥3,061,075 → ¥1,168,023 (TN: US$11,680.23)] (See Complaint Form No 2, 1 (3) A [Pg 29] below)

2.2.1

Medical Related Expenses [¥200,251 (TN: US$2,002.51)] (No change)

2.2.2

Return Travel Expenses [¥517,120 → ¥828,652 (TN: US$8,286.52)]

(A)

Previous Return Travel Expenses [¥517,120 (TN: US$5,171.20)] (no change)

(B)

Additional Return Travel Expenses [¥153,660 (TN: US$1,536.60)] (Evidence Article Koh C14-1)

On October 7th, 2007 the plaintiff had to cease employment again and make another return home due to the long term effects of the said incident. Subsequently, the additional cost of ¥153,660 (TN: US$1,536.60) was borne by way of Re-return Travel Expenses.

(C)

Japan Travel Expenses for Testifying [¥157,872 (TN: US$1,578.72)] (See Evidence Article Koh C14-2).

The plaintiff returned to Japan to testify in this case necessitating an airfare of $NZ2,428.80 (¥157,872 conversion) (See Evidence Article Koh C14-2).

2.2.3

Compensation Claim Related Expenses [¥39,100 → ¥139,120 (TN: US$1,391.20)]

[See appendix] (Evidence Articles Koh C15-1 through 16-1).

These were expenses borne by the need to commute between the plaintiff’s place of residence and the lawyer’s office, related accommodations, diagnosis form requests etc.

Due to the complexities, these have been appended. NB: There is no claim on items for which there is no supporting evidence.

2.2.4

Lawyer’s Expenses [¥2,304,604 → ¥0 (TN: US$0)]

There is no claim on lawyer’s expenses.

2.2.5

Subtotal [¥3,061,075 → ¥1,168,023 (TN: US$11,680.23)]

Inclusive above are item numbers (1) through (4) totaling: ¥1,168,023 (TN: US$11,680.23)

Top of Page

2.3 Intangible Losses

Intangible Loses [¥17,769,575 → ¥25,240,825 (TN: US$252,408.25)] (Refer Complaint Form. Clause 2, 1 (3) B [Pg 31] below)

2.3.1

Regarding the Plaintiff’s Base Salary

With regards to the plaintiff’s original base salary line, this was based on his annual salary at the Saitama International Association where he was working (¥3,600,000 – See Evidence Article Koh C3, page 4, clause 4) (TN: US$36,000). This is quite valid as compensation for damages relating to actual income reduction due to leave of absence from work.

However, to assume that his income earning potential would have remained the same as it was at the time of the incident, without any increases whatsoever, after such time that his condition had stabilized, would be totally unrealistic. If there is the possibility that he could have ended up earning the average income, then the base figure should be set to the total average income.

For example, in the Tokyo District Court Case: Heisei 10 (1998) (Wa) No. 17974 (Civil Case for Traffic Accident Citation 37, Volume One, Page 239) the plaintiff in this incident:

(1)

Had no merit of employment between the time he discontinued university and the time he was employed by a securities company in West Germany.

(2)

At age 30, the plaintiff’s annual income was ¥4,443,400 (TN: US$44,434) as at the 1996 financial year, which according to the remuneration census of that same year, was well below the average of ¥5,218,100 (TN: US$52,181) for that of males the same age with the same academic background.

Despite this, there was sufficient predictability to suggest that he could have been receiving periodic increases in annual salary, and subsequently, it was granted that it was possible for him to have been earning the average amount of ¥5,390,600 (TN: US$53,906) for people from the same generation with a college education, as shown in the remuneration census, which resulted in the base salary for his loss in income earning potential being calculated against this amount.

The Plaintiff in This Case:

(1)

Originally the plaintiff was engaged in employment in New Zealand. In 1994, at age 28, the plaintiff made his way into the Japanese work scene by starting work at an English school in Nagoya leading towards what became a future rich in merit for employment.

In fact, if it were not for this incident, he would have continued working at the Saitama International Association (Evidence Article Koh C3) and there was scope for salary increases based on term of service. Furthermore, this even more so, given that at the time, unlike now, foreigners proficient in Japanese were a rare commodity and could have basically named their own prices.

(2)

The plaintiff’s annual salary at the time of the incident in 2000, at age 34, was ¥3,600,000 (TN: US$36,000), which is lower than the average shown in the remuneration census of ¥5,775,200 (TN: US$57,752) for males of the same generation with the same academic background, namely a university degree.

However, this is because at the time the plaintiff was exploring different pathways and was willing to accept a lower than average income whilst accumulating more experience before settling down. In New Zealand it is common for people to do this and then to secure a more stable career from about one’s mid-thirties onward. Subsequently, there was sufficient scope for the plaintiff to have settled into working at any one company where he could have received regular incremental pay increases.

(3)

The plaintiff possesses outstanding Japanese language ability (Evidence Article Koh C17-12), and he received specialist training in Japanese culture at university (Evidence Article Koh C18). His ability is not simply limited to Japanese language ability alone but it has also been highly commended across a complete range of skills including professional communication know-how etc (Evidence Article Koh C19).

In fact, he received a recommendation from the International Affairs Division of the Miyazaki Regional Government Office to take up the position of Program Manager (Evidence Article Koh C20-1) at the Council of Local Authorities for International Relations (Evidence Article Koh C20-2). (The income for this position was ¥6,600,000 (TN: US$66,000), although he was not selected on this occasion).

As above, there was sufficient scope for the plaintiff, who possesses outstanding abilities, to have been able to earn the average annual salary.

2.3.2

Damages from Previous Lost Work Time [¥9,128,225 (TN: US$91,282.25)] (no change)

2.3.3

Loss in Future Income Earning Potential Due to Long Term Effects [¥8,641,350 → ¥16,112,600 (TN: US$161,126.00)]

- The base salary has been set at ¥6,712,600 (TN: US$67,126) which is what it should be in accordance to the total average annual income for all people with a university education as at the year 2000.

- Loss in Work Ability (15 percent [no change])

Base salary of ¥6,712,600 (TN: US$67,126) × 15% Loss in Work Ability × 16.0025 (TN: years) = ¥16,112,757 (TN: US$161,127.57) loss in income earning potential.

2.3.4

Subtotal [¥17,769,575 → ¥25,240,825 (TN: US$252,408.25)]

As above, items 2.3.1 ~ 2.3.3 total ¥25,240,825 (TN: US$252,408.25).

Top of Page

2.4 Pain and Suffering Payment

Damages for Pain and Suffering [¥4,520,000 (TN: US$45,200)] (no change)

Top of Page

Clause 3: Conclusion

As above, the Plaintiff’s claim in this case amounts to 30,928,848 yen (TN: US$309,288.48).

Therefore, the plaintiff hereby claims this amount against the defendant pursuant to clause one of this claim form.

Top of Page

(Penalty Interest Fee Calculations – Pursuant to Clause 1 Above)

March 25th, 2006 to September 25th, 2008 = 2½ years.

September 26th, 2008 to October 2011 (Supreme Court ruling) = 3 years.

No final payment was ever made but proceedings concluded with the Supreme Court ruling in October 2011 creating a 3 year period for the latter figure.

As above, a penalty interest rate of 5% was included in the claim, based on Japanese law, to cover the very many ongoing miscellaneous expenses during litigation, and the monumental amount of work hours (approx. 20 hrs pw) that went into preparations (for almost a 10 year period when pre court preparations are included).

Penalty Interest Rates

¥25,350,650 × 5% × 2.5 years = ¥3,168,831 (US$31,688.31)

¥30,928,848 × 5% × 3.0 years = ¥4,639,327 (US$46,393.27)

¥7,808,158 (US$78,081.58)

Total Claim Amount

¥30,928,848 (US$309,288.48) Principal Claim Amount

+ ¥07,808,158 (US$078,081.58) Penalty Interest Amount

¥38,737,006 (US$387,370.06) Grand Total for Damages

(NB: The above figures are given on a dollar to yen basis. Legal expenses are shown seperately in the Legal Aid Loan Recall Form.)

Top of Page

Justice or Not?

- I think the ultimate discrepancy in the High Court Verdict is that the Judge failed to rule out the fact I was dependent in terms of the DSM-IV-TR (worldwide recognized diagnostic standard) which formed the overall basis for the entire case.

- Although the Judge addressed two of the criteria in tolerance (criteria 1) and withdrawal (criteria 2), albeit without any direct reference to the DSM-IV-TR itself, he completely failed to address the other three that were being claimed – effectively leaving them standing.

The primary language of this website is English. Japanese appears as translations only (except for some original court documents).

These translations have been done by many different translators including me. Therefore, there are differences in quality and styles.

Please understand that I am not native Japanese and subsequently there are parts that may sound unnatural in Japanese.

Some parts of this website still have not been translated into Japanese. If anyone (native Japanese) would like to help on a volunteer basis, please contact mentioning the part you would like to translate. Thank you.

“If any drug over time is going to just rob you of your identity [leading to] long, long term disaster, it has to be benzodiazepines.”

Dr John Marsden,

Institute of Psychiatry, London

November 1, 2007

“Benzos are responsible for more pain, unhappiness and damage than anything else in our society.”

Phil Woolas MP,

Deputy Leader of the House of Commons,

Oldham Chronicle, February 12, 2004

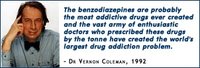

“The benzodiazepines are probably the most addictive drugs ever created and the vast army of enthusiastic doctors who prescribed these drugs by the tonne have created the world's largest drug addiction problem.”

The Drugs Myth, 1992

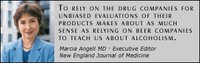

“To rely on the drug companies for unbiased evaluations of their products makes about as much sense as relying on beer companies to teach us about alcoholism.”

Marcia Angell MD

(Former) Executive Editor New England Journal of Medicine

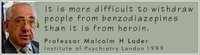

“It is more difficult to withdraw people from benzodiazepines than it is from heroin.”

Professor Malcolm H Lader

Institute of Psychiatry London

BBC Radio 4, Face The Facts

March 16, 1999

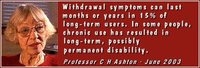

“Withdrawal symptoms can last months or years in 15% of long-term users. In some people, chronic use has resulted in long-term, possibly permanent disability.”

Professor C Heather Ashton

DM, FRCP,

Good Housekeeping, 2003

“Clearly, the aim of all involved in this sorry affair is the provision of justice for the victims of tranquillisers.”

THE WRITING IS

ON THE WALL

for benzodiazepine use

Dr Andrew Byrne

Redfern NSW Australia

Benzodiazepine Dependence, 1997

- Our key witness was twice denied the opportunity to testify – once by the Tokyo District Court and once by the Tokyo High Court.

- The Tokyo District Court judge raised an issue in the defense's favour only after proceedings had ended totally denying us any opportunity for rebuttal.

- The Tokyo High Court judge chose to use the package inserts from the drug companies to determine the amounts at which benzodiazepines could be deemed addictive, completely ignoring the extensive evidence (literature, expert opinions etc) submitted to the contrary.

- The courts made no issue over the prescribing doctor diagnosing me with one thing and treating me with drugs used for something completely different.

-

More than half the applied DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria for dependency were not addressed in the verdict.

- The presiding High Court judge was replaced half way through proceedings by a judge who knew absolutely nothing about the case or benzodiazepines before the verdict was delivered.